Considering the importance of the rope in climbing, it’s surprising how little most climbers understand their construction and ratings.

Below is a brief explanation of what the markings on the packaging of a new rope mean.

It would be easy to write at length on each of these markings and at times it’s been harder to make a concise but sufficient explanation.

What do all the markings mean?

What do all the markings mean?

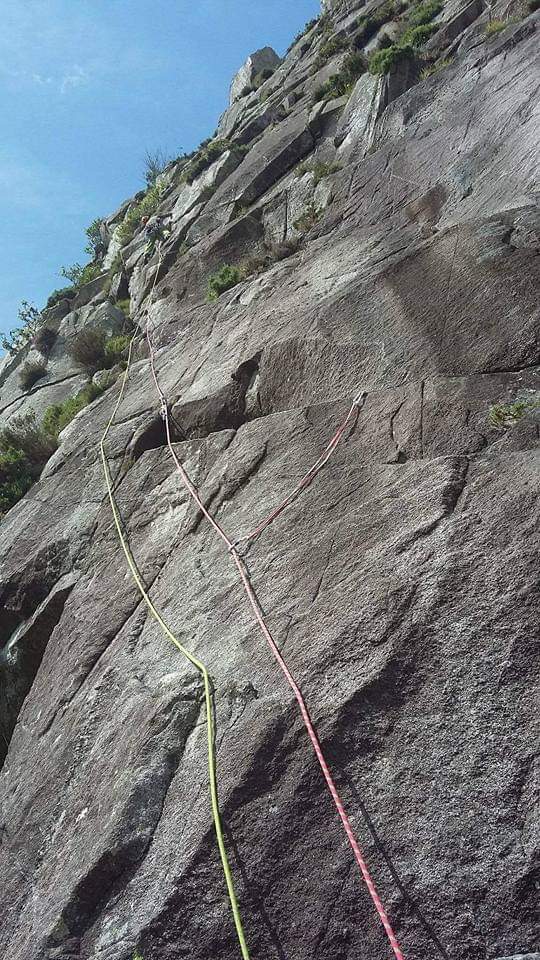

This particular rope will serve me well for climbing single pitch routes in the Burren during the summer but of less use to me at Dalkey, Glendalough or Scottish Winter. Let’s see why:

The 1 indicates that this is a single rated rope.

Single rope: designed to be used on its own.

Half/double ropes: designed to be used as a pair, with only one rope clipped into each piece of protection.

Twin ropes: designed to be used as a pair, clipping both ropes into the same piece of protection.

Triple rated ropes are designed to be used as single, twin or half ropes. As such are the ultimate multipurpose tool and are priced accordingly.

If you want to see the advantages of half/double ropes, you can read this blog post I wrote about them

UIAA Falls: 7-8

This does not mean that after experiencing 7-8 standard lead falls, your rope is no good and should be retired. A common misconception.

Modern ropes don’t generally break, they cut or abrade.

The kinds of forces used in testing are extremely severe and not generally the kind of forces the average lead fall can create.

All UIAA certified ropes undergo a similar test process. To pass, it must survive a minimum of 5 simulated falls without breaking. This rope has failed after 7-8 of those test falls.

Delving into those fall factor forces is separate a blog post in itself, so while it’s safe to say that this rope is perfectly strong enough to withstand a lot more than just 7-8 “normal” lead fall scenarios.

Maybe if I have had a couple of big whippers in a row then I’ll take a break from using this rope and allow it to shrink back to normal size.

If I was to have the kind of fall simulated in the test, I’d probably not be going for a second attempt at the climb.

A higher fall rating can however indicate a better quality of rope, with increased durability and lifespan.

Impact Force, 8.4kn.

This is the force transmitted from the rope to the climber under a fall, essentially, the ropes ability to absorb the energy of fall.

The lower the number the more pleasant the fall.

Again, it is tested using high fall factors and doesn’t allow for the forces being absorbed by the climbers and belayers bodies, rope slippage through the belay device etc, which would occur in a real-life fall and would also contribute to a comfortable “soft catch“.

This rating can be a consideration for the trad climber as the lower the IF number, the better the dissipation of the forces created during a fall and the less force transmitted into the placed protection.

A sports climber taking multiple lobs on a project might appreciate the comfort of a rope with a low IF number.

In the case of bottom/top-roping, you ideally want a higher IF number as the forces created during this type of fall are low and we probably want less stretch, to avoid the climber hitting their ankles off a ledge or the ground.

Elongation in Use, 6.5%

This is the amount of rope stretch created when hanging a static weight from the rope. In testing, they use a static weight of 80kg.

So if an 80kg person was to hang on the full length of this rope, it would stretch to become a 42.6-metre rope or 6.5% of the length of the rope.

The thinner the rope, the more likely it is to stretch further. A rope will stretch more when wet but it will lose its elasticity the more it is used.

proportion of Sheath, 40%

This is how much of the construction of the rope is made up of sheath and how much of it is made up of the inner core (60%).

The core is where the primary strength and elasticity of the rope is, but the sheath determines its ability to withstand abrasion and its durability.

Remember, ropes generally don’t break, they cut, so this is an important rating to take into consideration.

This is why I have one set of ropes of working with (these run over more edges and take more abuse) and a different set for personal climbing (these have less wear and tear but bigger falls).

UIAA water absorption, 46%

Wet ropes stretch more, get heavier/harder to use and can make using ascenders and Gris-Gris difficult, so it can be important that they are water repellent, especially in snow and ice conditions.

This particular rope has a high absorbency and wouldn’t be much good for ice climbing, but will be just fine for use at a short single pitch crag on dry summer days.

As per the UIAA test, a true water repellent rope should have a water absorption rating of 5% or less. Some “Dry” ropes don’t achieve this as they are only dry treated. Like your waterproof jacket, the treatment wears off over time.

Elongation at 1st fall, 31%

This is the percentage of stretch in the rope the first time a dynamic fall or load is applied to it. Like the elongation in use test above, an 80kg weight is used and replicates a severe fall scenario.

While a maximum 31% stretch may seem like a very high and worrying number, it will always be less in reality, where we won’t achieve the forces created in the UIAA test.

However, it might just make you think about not using your brand new ropes on a short lead climb where the crux is at the bottom of the route.

The elongation percentage will reduce over the life of a dynamic rope.

Sheath Slippage, 0%

The less slippage between the core and the sheath of the rope, the more durable it is.

We’ve all seen the ends of a rope in a climbing wall get bunched up and fat from this, or feel a thin spot on a rope where it’s been damaged, so you would think 0% is an ideal score here.

However, ropes with less slippage can be less pliable and soft to handle. Some sheath slippage can even be a good thing if the rope is running over a sharp edge as the load is spread across a greater area.

Any visible damage or alteration to the rope from sheath slippage should be treated with caution and cut from the rope or retire the rope completely.

Other markings

While length, diameter and weight per meter of the rope are self-explanatory markings, they are helpful to let us know what category and preferred use to put a rope into.

So what rope should you buy then?

There’s no point spending a fortune on ropes if your style of climbing doesn’t need all the design features possible for a rope.

A low price doesn’t mean low quality, it could just mean fewer options to use it.

If you climb exclusively indoors you shouldn’t be concerned about ratings like weight or water repellency and should go for a thick robust and competitively priced rope. The Beal Wall master perhaps.

If the majority of your climbing is on smaller single pitch trad routes, then any single rated 50m rope will get you through most days in Ireland and will be super affordable. Something like the Tendon Smart 10mm.

For sport, any single rated rope will do once its sufficiently long enough to let you climb AND lower off the route. If it’s a particularly long route then definitely thinner lighter ropes are better.

But if you intend to or do a lot of multi-pitching in Ireland then get a set of 60m half/double ropes as well as the above 50m rope and mix and match between the two sets. I use DMM Crux 9.1mm ropes and they are class.

If you intend to go to Scotland in the winter, bring doubles and make sure your ropes are proper dry ropes or at least dry treated.

However, if money isn’t an issue and you want simplicity and a great all-round option, get a set of triple rated 60m Beal Joker unicore Golden dry ropes to have the solution to all the above climbing scenarios.

Well all scenarios apart from a 30m+ sports climb that is.

I hope the above post is useful. Please feel free to contact me if you would like to discuss any aspect of this post.